Streetwear and Jiu-Jitsu - A Short Dissertation

Streetwear and the hype surrounding it is a fairly recent phenomenon that has been amplified through the proliferation of social media and 24/7 access to celebrities and news cycles. Fashion is highly disposable and pieces are acquired for an Instagram flex rather than long term utility which can give it a sense of futility and frivolity. However Streetwear is now an undeniable force, which cannot be ignored, with traditionally high fashion brands such as Louis Vuitton and Gucci doing collabs with traditionally urban labels and artists to generate the most hyped and anticipated drops of the season. Furthermore, with Supreme’s 50% acquisition by the Carlyle Group and StockX’s USD 110m cash injection by finance consortiums (valuing them both at USD1bn) the hype machine shows no sign of abating.

The streetwear drop cycle for fashion used to be able to be measured in quarters or tied to specific events. Now they come at a furious pace, barely giving the consumer a chance to catch their breath before their Instagram feeds assault them into pursuing the next release.

When considering the prevalent brands in jiu-jitsu today such as Shoyoroll, Storm, Scramble etc we can observe a similar pattern emerging of quick release cycles, collabs with streetwear labels and celebrity endorsement. Similarly, traditional streetwear brands such as Undefeated have made significant investments into the art with jiu-jitsu inspired lines of apparel and even a dedicated training facility which has jiu-jitsu as one of its major disciplines.

Why has there been a convergence in recent years of streetwear and jiu-jitsu? What is the appeal that brings both cultures together? Why jiu-jitsu and not Karate or even the root martial art of Judo? To understand that we need to go back to the ’90s when the basis of streetwear as we know it today were just starting to form.

Historically streetwear was rooted in the subcultures that birthed them and very rarely diffused outside of the orbit of immediate and active participants of said culture. Examples include Punks, Rockers, Mods, Skateboarders, Surfers and Hip Hop Heads to name a few. You had a genre and you stuck to it. Your identity was based on your apparel and demeanor which acted as an invitation or repellant to others depending on their tribal politics.

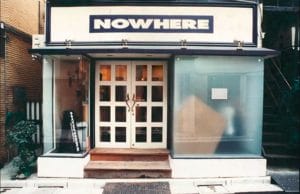

Information transmission was extremely lo-fi and ideas travelled by word of mouth, photocopied fan-zines, or physical trips to iconic boutiques (think “Collette” in Paris, “The Hideout” in London and “Nowhere” in Urahara district of Tokyo). There was a certain pleasure in the hunt for knowledge and new product information (which was anticipated with bated breath) was studied and obsessed over and over.

Nowhere – Urahara ’90s Tokyo

Colette – 1st Arrondissement Paris

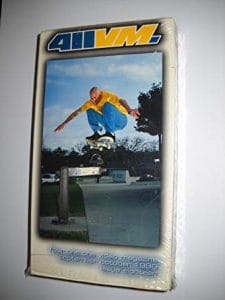

Skateboarding was one of the first cultures to bridge the gap between the different genres and show that it was ok to have interests (and be influenced) outside of your immediate circle. The introduction of 411VM (a monthly skateboard video magazine launched in the mid ’90s) that was only available from your local skateshop in VHS format was groundbreaking as it put skateboarding against the backdrop of Hip Hop, indie rock and Motown soundtracks rather than the typical punk playlists of the time. Skaters suddenly started to have a deeper and wider catalogue of styles to draw upon which was immediately reflected in their fashion, skate presence and even types of tricks performed.

411 Video Magazine was only available in VHS at local skateshops

’90s skate fashion transitioned very quickly from punk band t’s and oversized denim to Hip Hop inspired Polo Sport/Hilfiger windbreakers and fitted khakis. Skateboarders also began emulating the swagger and attitude of the groups like Wu Tang and Souls of Mischief with smooth pushing and big stylised tricks. The gritty cityscapes with its unpredictable obstacles became the skateboarder’s environment of choice rather than the safe uniformity of the skateparks. This new wave of skateboarding formed the ethos of Supreme and Zoo York whose early videos documented the frenetic energy and exhilarating danger of ’90s New York street skating.

Around this period, Tokyo cast its otaku-eye over the nascent culture with Japanese kids collecting and cataloging sneakers and denim before their Western counterparts knew what was up. These kids would make trips to American factory outlets and skateshops, build connections with OGs like Stussy and Jebbia then hoover up all early Air Force 1s, Dunks and skate apparel to bring back to Tokyo and sell out at massive markups. It didn’t take long for them to move from consumer and resellers to do what only Japan could do by obsessively reverse engineering and, dare we say, improving the production, branding and quality of what was now commonly known as Streetwear. (That’s one of the main reasons why there are more Supreme and Undefeated stores in Japan than the rest of the world combined).

Supreme – Lafayette Street New York

Undefeated -La Brea Los Angeles

This was all still in the pre internet era and, in order to discover and learn about these products, one had to make the pilgrimage to Tokyo (even for an American to learn about their own archives). There was a grind to participating in the culture and the reward was to be only one of the few in the know. If you speak to the grownups who participated in the culture of that period they will always speak fondly of that delight of exploring Tokyo’s Urahara to find out what’s cool or up and coming and having their minds blown in the process.

Neighborhood – Urahara Tokyo

FXXking Rabbits – Urahara Tokyo

It was the Japanese discipline towards maintaining consistent narratives through its seasonal drops, callbacks to their archives and openness to work with other brands that have influenced what we take for granted today such as the staple design (e.g. box-logo tee), collaborations (or what Japan originally termed double-label) and cutting edge concept brick and mortar spaces.

The mid-2000s till today saw another seismic shift in technology, geopolitics, and tastes (which in itself deserves another article) bringing us to the present. While there are many different styles that now fall under the umbrella of “streetwear”, what we presented is how modern-day streetwear has borrowed heavily from the wabi-sabi nature of skateboarding where eclecticism is celebrated and genres are cross-pollinated into new and exciting forms.

Jiu-jitsu has gone through similar transformations with its origins from Japan, modification in Brazil and widespread exposure in the US with its efficacy proven in unarmed combat through the early UFCs. Jiu-jitsu has been appropriated, re-interpreted and re-presented by every culture that it has touched where it is now on it’s way to being a truly global martial art. With so many forms of combat available such as Karate, Tae Kwon Do and even Judo, why has it really only been jiu-jitsu that has managed to cross the threshold into the domain of fashion/streetwear, i.e. what makes it cool? Well let’s list them:

- With fashion and trends moving at the speed of light and access to the hype-est apparel available at the click of a re-sellers button, jiu-jitsu has an amazing ability to keep us grounded. The most coveted jiu-jitsu accessory of all is the stripe/belt, which (unlike sneakers, isn’t made artificially scarce) can’t be bought with anything other than time and dedication; thus becoming priceless to the bearer. There is an ostensibly lo-fi element to jiu-jitsu where it’s about the journey, the experience rather than the product.

- Similar to how skateboarding is a form of personal expression, jiu-jitsu presents a canvas where the way one moves and style of fighting, projects one’s creative individuality. Unlike skateboarding however, jiu-jitsu can be practiced well into one’s golden years giving it an evergreen quality that appeals to the grown up skater and older creatives such as Anthony Bourdain (Rest in Peace).

- Jiu-jitsu is able to be safely practiced at a 100% intensity against a 100% resisting opponent. The non-linear problem solving skills that one must develop and adapt depending on the situation and opponent is extremely addictive. Every sparring session presents a new puzzle which must be studied and understood before being unlocked. This is similar to the creative process where design doesn’t follow a straight a to b path but must involve deep understanding of rules and principles in order to subvert them and create an exciting new concept.

- Authenticity – In jiu-jitsu there is nowhere to hide and you can’t fake it. A lot of fashion relies on hype over substance. Some brands seemingly come out of nowhere based upon the chance anointing by a celebrity and leapfrog other brands who have been grinding for years. You can’t show up to jiu-jitsu class on day one with a fresh gi and start handling blackbelts. There is a dignity to paying your dues and rightfully earning what’s yours. Jiu-jitsu is the epitome of authenticity which is what creatives crave.

- Entry to an exclusive underground club – No matter where in the world you go there will be a group of like minded people speaking the same language as you and experimenting with the arcane secrets of strangulation and joint hyper-extension. This is akin to the old days of venturing to a new city and discovering a boutique of curated brands then developing an instant brother/sisterhood via a shared aesthetic ethos. Both experiences rely on a process of physical discovery and a purely analog system of communication which creates deeper and more meaningful connections.

These are only some of the numerous qualities/parallels of jiu-jitsu that draw creatives to practice The Gentle Art. While the purity and the freedom of expression of jiu-jitsu provides an additional outlet for creatives, they will also seek to contribute to the culture with their resources in marketing, design and branding in order to give back to the sport that has given so much to them. This ensures that fashion will continue to have a larger influence on jiu-jitsu in the coming years which will in turn drive more interest and participation in mainstream culture. We will be eagerly watching this space.

Notable brands merging streetwear and jiu-jitsu:

Undefeated and UACTP (Undefeated Action Capabilities Training Program)

https://www.uactp.com

https://undefeated.com

UACTP – DTLA

UACTP – DTLA

“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives, it is the one that is most adaptable to change” UACTP – DTLA

Shoyoroll

www.shoyoroll.com

Shoyoroll and the Heartbreakers – Trunk Hotel Shibuya

Shoyoroll and the Heartbreakers – Trunk Hotel Shibuya

Lucas Lepri for Shoyoroll and the Heartbreakers – Trunk Hotel Shibuya

Rats x Krazy Bee Gym

http://www.rats.jp/

Rats x Krazy Bee – Tokyo

Rats x Krazy Bee – Tokyo

Rats x Krazy Bee – Tokyo

Notable Creatives who train jiu-jitsu:

Angelo Baque (Former Creative Director of Supreme and Founder of Awake clothing)

Julien Cahn (Marketing Director of Supreme)

Masafumi Watanabe (Former designer of Tenderloin and Founder of Bedwin and the Heartbreakers)

Kenneth Cappello (Fashion Photographer)

Magnus Unnar (Fashion Photographer)

Flo Kohl (Fashion Photographer)

Gardar Eide Einarsson (Fine Artist)

James Bond (Founder of Undefeated and UACTP training facility downtown LA)

Rob Abeyta (Founder DualForces and Creative Director of Undefeated)

Helen Cho (Producer of My Next Guest with David Letterman)

Anthony Van Engelen (Owner of Fucking Awesome skateboards)

Brian Woo (Tattoo Artist – Dr Woo)

Words by Brendan Foong (Program Director of The Gentle Art Academy)

with special thanks to Flo Kohl and Rob Abeyta

www.thegentleart.co

https://www.instagram.com/thegentleartacademy

https://www.facebook.com/thegentleartacademy