Getting A Grip On Heat.

How to submit food with the proper techni-heat

There is the saying, “If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” Let’s go ahead and smash past the naysayers and learn how to, not only handle the heat in our kitchens, but master it. We spend our days in hot, humid and stuffy gyms with pounds of non-breathable fabric on. Not only are we spending time there, we are trying to work up a sweat. How do we survive? Turning a fan on, drinking cold water or sitting out a round. Who am I kidding? None of us do this! So, how does this relate to cooking? Well, all of those steps are a form of “heat management.” With cooking, the skill that will get your cooking up on the podium with a gold medal around its neck is also “heat management.” Knowing how to utilize, implement and control the heat is possibly the most crucial skill you can have. It can take years to master, but only a few minutes of reading to understand. Understanding the basic methods of using heat within cooking is as simple as learning an armbar, triangle or omoplata. With that being said, let’s get cooking!

The Concept

When we gather all of our ingredients to make a dish, the only thing we truly have control over, flavor-wise, is how we cook it. A steak will taste like a steak. The way we apply heat to it is how we can enhance or ruin the flavor of the steak. For example, which would you rather have? A perfectly pan-seared, dry, aged rib eye steak cooked medium-rare, or the same steak boiled in water? Exactly, on the flip side of the coin, you wouldn’t want pan-seared pork shoulder because it would be like chewing on a gi, as well as bland, rather than the succulent pork shoulder braised in stock with vegetables and spices. Not all ingredients are treated equally, thus they should not be cooked equally. The same goes with submissions, you do not try and slap on a rear-naked from bottom of the mount.

The Techni-Heats

Cooking is not rocket science or the worm guard. It is simple, and as a chef I used to work with would say, “It’s just cooking.” Wow, that doesn’t have the same impact when it’s not being screamed across the kitchen, in the middle of a Friday night dinner service in Manhattan. I am not here to yell, I practice the gentle (culinary) art. The primary methods of using heat are broken down into 5 categories:

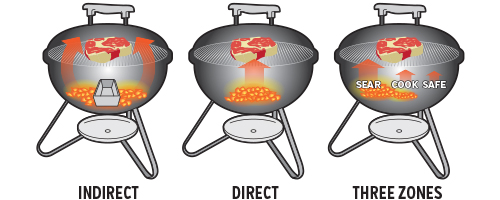

Direct Heat Method:

Direct heat cooking is pretty, dare I say, direct. It involves cooking with your ingredient in direct contact with the heat or “directly” above it. The primary benefit to direct heat is that it is fast and develops the delicious seared flavor. Also known as the Maillard Reaction, which I have mentioned in previous articles. And if on the grill, you develop charred and smoky flavors from being in close contact with the source of the heat itself. This is best use for any food that can be cooked in less than 15 minutes.

Foods and Cooking Methods for Direct Heat

Sauté, broiling, pan-seared, and grilling/BBQ.

Burgers, eggs, sausages, and vegetables, tender meats; chicken breast, legs, steak, pork chops, fish and other seafood that cooks quickly

Indirect Heat Method:

With an indirect heat method, you are focusing on cooking the ingredients, not directly over the heat source or in contact with it. Primarily used in “low and slow” cooking recipes because without direct contact, there is no way to burn or crisp the outside of your ingredient. That being said, you will not get the same flavors as with direct heat. Used for delicate ingredients that take a long time to break down.

Foods and Cooking Methods for Indirect Heat

Baking, smoking, slow cookers

Tougher meats; pork or beef shoulder, ribs, brisket, fish, such as baked salmon, cod or halibut, vegetables, potatoes, and pastries

Dry Heat Method:

Without the use of any water, we find ourselves using “dry heat.” Have you ever been to Arizona in the summer? Then you know what I’m talking about. The dry heat method is when we use ambient heat or direct heat, usually at high temperatures, to cook our food. Any method using oil is still considered dry heat, especially since oil and water do not mix, unless you want to use the dry heat method on yourself and your surroundings. These methods are best used on foods to develop flavor through changing molecules of the outside of the food. Once again, the Maillard Reaction shows up. To get “browning” you must use dry heat.

Cooking Methods for Dry Heat

Sautéing, frying, pan-searing, grilling, broiling, roasting, and baking. [/double_paragraph][double_paragraph]

Wet Heat Method:

Take a wild guess. Any cooking method that uses water as the primary heating source rather than open air or direct heat is considered wet. This one is pretty simple and very commonly used, but note: you will never develop rich brown or roasted flavors using only wet heat. Tougher meats take longer to become tender and require long term cooking at lower temperatures. If you are cooking something for a long time, it will lose moisture, if you have no liquid for it to reabsorb you will be making jerky and it won’t be as good as juicy, tender, braised meat.

Cooking Methods for Wet Heat

Boiling, simmering, blanching, steaming, poaching, stewing and braising. [/double_paragraph] [/row]

Combination Cooking:

Sometimes you just need the best of both worlds. Combination cooking can occur with any combination of cooking methods. Go figure, right? There are times when you want to get a good sear on the short ribs you’re going to be braising because we want that flavor, but cannot get browning within the wet heat method. Now, if we think about it, what is that also combining? That’s right, direct and indirect heat. The same goes for finishing a thick cut steak on the top rack of the BBQ after we get good grill marks on it, but do not want it to be as tough as shoe leather. This is how you chain your attacks together flawlessly and instead of being a one trick pony, you are now a Swiss army knife of ways to cook.

Combination Cooking Examples

Dry to wet: Searing for flavor, braising for temperature

Wet to dry: Blanching for temperature, searing for flavor

Indirect then direct: Roasting covered for temperature, uncovering for flavor

Direct then indirect: Grilling for flavor, finishing for temperature.

Conclusion

Cooking is the same as Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu; the devil is in the details. And with the devil comes heat. Knowing how to understand and control the heat is fundamental to your success. Whether you are simply struggling through your dinner after class, or your BBQ in the park with your training partners and family, the methods never change. What does change is the outcome, based on how you use the methods. Treat your flavors as you would your submissions, set them up properly and utilize the proper techniques.

Eat well, train hard, OSS.

Grappler Gourmet