Can’t we all just get along? Pacifism and Jiu-Jitsu

I teach jiu-jitsu classes. I train MMA fighters. I referee jiu-jitsu matches. I have devoted a writing career to fighting. I even worked the door at a nightclub in Pittsburgh for a brief period to earn some extra money.

And I consider myself a practical pacifist.

That perplexes many of the people I talk to, both inside and outside of our sport. As contradictory as this philosophy and my career may seem, this to me is an important, deliberate choice that we do not discuss enough on the mats or in our community in general.

Defining Violence

Traditionally, pacifism is strictly anti-violence. At the same time, I cannot deny that jiu-jitsu is a violent art. I treasure a strong cross face and am well-aware that what I practice is specifically designed to dismantle the human body in the most efficient manner possible. My life pursuit, it would seem, is to master the ability to systematically destroy every functioning joint that a person has. When I train MMA fighters, we talk about strikes as well, using the control of jiu-jitsu positioning to launch vicious punches and knees for maximum damage.

That is violence. Within the context of sport, however, it is a completely different kind of violence from a mugging. The intentions are completely different and our community is instinctively aware of the divide. In almost the same moment we can applaud a beautifully executed leg lock and shake our head in disgust at a fighter’s refusal to release the submission when his opponent has clearly conceded.

We recognize that consensual violence between two rational adults can be quite safe and even healthy. The majority of jiu-jiteiros even feel a deep sense of guilt and self-disgust when they accidentally injure a training partner. There is generally no active malice. The violence is scientific and controlled. Within the boundaries of play—as intense as that play might get—we can participate in an extremely violent pastime without any intention of inflicting lasting harm.

Jiu-jiteiros then can proudly champion sportive violence while remaining vehemently opposed to malicious violence. Therefore, we can at once love fighting and still champion non-violence.

Jiu-Jitsu in the Streets, Then and Now

In practice, I avoid violent confrontations at all costs. Recently, I was at a local Mexican restaurant and as my wife and I waited to pay I noticed a gentleman that looked like John Hackleman, the famed coach of Chuck Liddell for many years. I was a ways south of the city, had enjoyed at least one margarita, was tired from a long work week and was pretty far from where the Hackleman doppelganger sat.

So like the socially awkward man-child that I am, I stared a bit too long to see if it was in fact the Pit Master. A burly man with tattoos looked at me, narrowed his eyes, and said, “You got a problem?”

I have plenty of problems, but none of those were at play at this exact moment with the exception of my social ineptitude. In that cinematic fight-scene way, everything slowed down. A good portion of the restaurant was now looking at us. Another human being made me look and feel small in front of a person I cared very much about. He postured and his hands clenched. In a small way, this was a challenge. I could stand up for myself against someone who clearly wanted to fight or I could pay my bill and leave. I left and now the consequences of this event only live on in my memory.

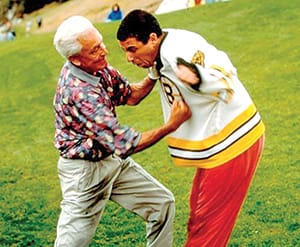

This story is hardly on par with being assaulted in a parking garage or facing off against a knife-wielding attacker, but if this confrontation had taken place on a beach in Brazil in the 90s my jiu-jitsu might have been featured on a grainy VHS highlight tape that underground fight fans copied and traded.

That reality, the fact that our sport has its roots in challenge matches and street fights, makes it difficult to authentically preach non-violence. It was not too long ago that our fighting heroes would stomp on an unconscious opponent at the end of a fight or allegedly use a younger sister to spark a fight in a night club for the fun of it. Even now, when the viral video of a basketball trash-talking session turning into a fight spread across the web, it took a depressingly long amount of time for anyone to point out that the jiu-jiteiro in the video made no attempt to deescalate the rising tension.

Was it cool to see 50/50 guard in a street fight? I suppose it satisfied some degree of curiosity about the position, but aren’t we beyond the point of needing to see jiu-jitsu prove itself in street fights? I’d like to think so.

Practical Pacifism

I do not deny that we live in a violent world with dangerous people. I openly recognize that the purest forms of pacifism, while completely admirable, are probably not the best self-defense solutions. The moral victory of enduring an assault, in my mind, is almost as unproductive as a philosophy that skews toward the uber-violent end of the spectrum. Before the historians in the audience send me hate mail: I am speaking specifically about one-to-one violence, not non-violent activism in a grander political context like we saw with Gandhi or Martin Luther King Jr.

If I or someone I love is attacked, I will defend myself and/or them. What I love about Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, however, is that I can match the intensity of my response with the intensity of the situation. In the case of striking arts like Krav Maga, the reaction is to always assume that your life is in danger so bite his balls and scoop out his retinas. With jiu-jitsu, I can subdue a friend that has had too much to drink or I can permanently cripple someone that has every intention of ending my life.

In this way, jiu-jitsu gives me the tools to practice pacifism in the most practical way that I can imagine. I only need to be as violent as the situation warrants. I can use what I know about violence to attempt to defuse the problem rather than escalating the situation with my own aggression.

Don’t Get Dead

Ultimately though, the more I train the more I appreciate just how fragile the human body is. I was raised by Rambo movies and spent many nights stealthily watching Tango & Cash while my parents slept, so for some time I had this idea that fights were these grand endeavors where two guys could duke it out for 10 minutes and then limp away to recover.

I now know that our bodies are horribly designed fighting machines. We break easily and it is far too easy to die, even if you are a talented fighter.

When I was a freshman in college, I faced this reality when my childhood neighbor (who was a year older than me and attended a larger school in another state) got into a fight at a party. The argument escalated, it got physical and the night ended with my neighbor bleeding out on a trashy college town porch. One day R.J. was my cocky soccer team captain, the next day I was looking down at him in a coffin.

For many months after that, I obsessed over knife defense and the more I dug into the subject the more I had to accept that death was a much closer probability than I had originally thought. A knife is a simple weapon to wield and we are covered in soft flesh and essential life-sustaining pieces. Even without knives involved, hitting your head on the pavement or the edge of the bar is a quick way to go dark forever. Factor in the potential for broken bottles or buddies that sneak up behind you or the random patriot with a handgun tucked in his pants and you have a slew of potential life-enders that have almost nothing to do with how fit you are or how long you have trained.

In the end, the best form of self-defense is to avoid violence altogether. That’s an old saying, but so few in our community actively live and promote that pacifist notion. If one of the goals of jiu-jitsu is to protect ourselves and the ones we love from violence, we need to talk more about the value of leaving machismo behind and seeking peaceful resolutions.

To end, let me share one of my favorite pieces of hate mail: “Marshal. You seem like a pussy.”

There, I saved you an email.