Dangers Of The Heel Hook

Just saying the term “heel hook” will send shivers down any grappler’s spine, from head to heel. In many sanctioned competitions, the heel hook is not legal in any division. If not released in time, a heel hook can do some severe damage. In this article I’m going to share with you the dangers of this rightly feared move.

What Does the Research Say?

Current research suggests knee joint injuries are second to the elbow joint at large scale BJJ events. As this may be the case, the mechanism of injury from reported knee injuries are due to straight knee bar (terminal knee-end range) and/or nonspecific twists related to De La Riva guard and takedowns. A question yet answered, is the heel hook submission and its relevant data on BJJ knee joint injuries. Since the heel hook is illegal at most jiu-jitsu venues, such as the International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation and North American Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation events, reported knee injuries might still remain a distant second to the elbow joint. However, heel hooks are legal at many no-gi grappling tournaments. While BJJ fighters may suffer specific ligament and meniscal structural damage from legal reported knee submission positions, the literature still is absent when discussing the heel hook and the damage it can generate.

Anatomy of the Heel Hook Injury

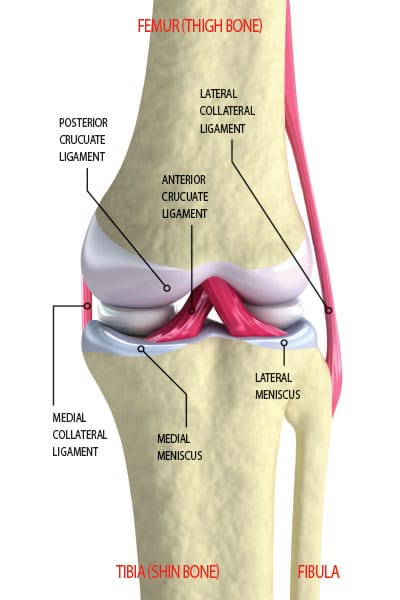

Lateral Joint Line: This area of the knee is considered the lateral joint line. Structures that are injured due to a heel hook may incorporate the Lateral Collateral Ligament, Lateral Meniscus, in addition to, Posterior Cruciate Ligament and Arcuate Ligament Complex.

Although the application of the heel hook is applied at the heel of the ankle, especially, the subtalar joint, it is the rotation of the tibia on the femur that produces structural knee damage. As a fighter locks his opponent’s’ heel into place within the crease of his elbow, the tibia will internally rotate on a relatively fixed femur. These high rotational forces applied to the heel act as a long lever arm that will generate increased torque and sheer at the knee joint. Since the knee joints’ primary range of motion is limited to flexion and extension, with a minimal amount of tibial rotation, there is little room for more than a few degrees of internal rotation. Structurally, the femur and the tibia articulate with each other through ligamentous tissue for support. Although there are several areas of tendon crossing over the knee joint for dynamic support, the knee joint is susceptible to injury due to its weak infrastructure. Because of the anatomy of the knee and the leverage of its long bones, knee injuries are prevalent with forceful tibial rotation.

What Structures are Damaged in the Heel Hook?

It may be hard to specifically determine which knee structure will be damaged during a fierce heel hook, but one could hypothesize it may be multiple. With violent tibial internal rotation and knee valgus (the knee joint collapsing towards the mid line of the body), the Anterior and Posterior Cruciate ligaments, as well as the Medial Collateral ligament, can be damaged. Additionally, either menisci (medial and lateral) can also be involved. As ligaments are responsible for attaching bone to bone, the static properties of a ligament have incremental dynamic properties. In other words, ligaments do not stretch like tendons do. Therefore, once a ligament reaches its peak limited tensile length, it will tear. A good analogy of ligaments and tendons are; ligaments are like rope and tendons are like rubber bands. While this is the general injury mechanism for a ligament injury, low loads or smaller forces on a ligament over time may cause a phenomenon known as “tissue creep.”

Tissue creep is when a ligament gains more stretch or length within a joint. Specially, if a ligament is placed in a position of strain or stress for prolonged periods of time, the ligamentous tissue will incrementally elongate under the stress and not tear. For example, if a fighter was involved in multiple heel hooks over time, and understood how to combat the applied position, his knee may incur some gained internal tibial rotation. While this is not recommended as a choice of defense, ligaments will react to less forceful loads with creep. Tissue creep can also be seen in many other joints of the body from sustained positions, such as the ankle, hip, and shoulder.

How do I Tear my Knee Structures?

Damaged ligament tissue, in addition to menisci, will create an audible popping sound when tearing. This may be the telltale sign that a person has just incurred a serious knee injury. This is not always the case, as other signs and symptoms include pain, swelling, redness, and inability to weight bear. These structures are considered avascular, meaning; there is limited blood supply to major areas of ligaments and menisci. This is a primary reason why some significant knee injuries are not followed by swelling. Orthopedic evaluation by a qualified athletic trainer, physical therapist, or orthopedic physician is warranted immediately. The quicker the medical evaluation and diagnosis, the faster the treatment protocol and return to training.

Understanding your Risk

While injuries from heel hooks still are not tabulated through data collection or seen in the literature, some practicing BJJ fighters are aware of the positional dangers when caught in it. Simply, the feel of an applied heel hook may be sufficient enough to make a person tap. Rotational torque in the knee at high force leaves little time to make proper decisions to combat the position and decrease your chance of injury, thus reducing your risk.

Heel Hook Rehab

These are some different exercises you can do to help rehab injury caused by a heel hook.

Double Leg Glute Bridge

The purpose of this one is to engage glutes to control for knee alignment. At the end Focus on engaging glutes at top of bridge.

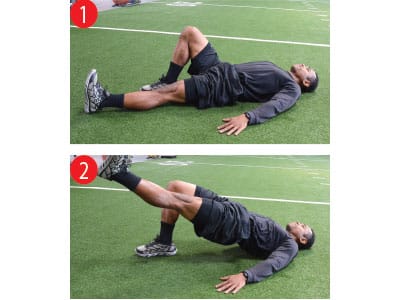

Single Leg Glute Bridge

Once you have achieved strong hip control with double leg glute bridge, proceed to single leg.

At the end keep hips even during leg drive. Keep straight leg level with other leg.

Squat with Band Resistance

Once you have achieved strength with ground exercises, proceed to standing squat with band just below patella level. Start will light band resistance. Squat down while maintaining force against band. This will aid in glute activation. Make sure knees guide over 2nd and 3rd toes during squat. Attempt to squat below parallel with torso in line with shin angle.

Single Leg Romanian Dead Lift (RDL)

Once you have achieved appropriate form and strength during the squat pattern, you can proceed to single leg RDL. Single leg RDL is excellent for glute activation, knee control, and over all motor control of the lumbopelvic girdle. If done well, the leg will swing straight back while pivoting over stance leg.

At the end point of the single leg RDL is torso and leg achieving 70 degrees of hip flexion or torso and leg relatively close to parallel with floor.

Single Leg RDL with Kettle Bell

The position and form is same as single leg RDL, but with kettle bell in hand. Place kettle bell in hand that is opposite of stance leg. Form is same. Make sure that bell is held firmly with shoulders back.